Clik here to view.

Ants in his pants: Alibaba and Ant Financial founder Jack Ma, 52, is China’s richest tech boss but he isn’t slowing down. Photo credit: Alibaba.

Jack Ma has built up not one but two tech giants. Alongside his US$250 billion Alibaba empire there’s Ant Financial, maker of China’s top mobile wallet app.

Valued at an estimated US$60 billion ahead of a possible IPO this year, Ant Financial is now on a streak of overseas deals as the firm takes its fintech services into new markets.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

From those moves into India, Thailand, the Philippines, the US, and – earlier this week – South Korea, we now have a clearer snapshot of Jack Ma’s playbook.

1. Go after people not served by banks. There are a lot of them.

When Ant Financial last month picked up US-based Moneygram for US$880 million, it wasn’t going after American consumers – it had its eye on the migrant workers who need to wire home money to the 200 countries where it has outlets.

The US is the biggest source country for remittances. Globally, migrant workers sent home US$432 billion in 2015 – well up on US$332 billion five years prior, according to the World Bank.

Clik here to view.

A Moneygram outlet in Beirut. Photo credit: Panoramio.

Only 12 percent of Moneygram’s revenue from transfers derives from US consumers sending cash within the country – 38 percent of it is outbound transfers, while the remaining half is all outside the US. As with all major money wiring services, the recipients don’t need to have a bank account.

In this way, Ant Financial is after the so-called unbanked population – people with little or nothing in the way of financial services, often not even debit or credit cards, from the traditional banking sector.

Ant’s four investments for expansion across Asia further prove that.

India has 233 million unbanked people, while there are a further 370 million across Southeast Asia.

2. Focus on mobile. Seek out people that are mobile-first.

Ant’s new Asian territories are also emerging markets where there’s rapid adoption of smartphones and internet usage. Being relatively late to the web, people are skipping past PCs and laptops and going straight for mobiles.

It’s less monolithic, more cautious.

In Korea, Thailand, and Philippines, Ant Financial chose working partners that are focused on mobile apps and services.

While Moneygram is a lot more old-skool, with over 350,000 agent locations around the world, it’s gradually getting there. Of the 225,000 new active customers seen in its latest earnings report, 60 percent of their transactions are on phones or tablets.

3. Pick major partners. They’re much safer bets than startups.

Ant Financial has avoided acquisitions in its four Asia gambits, instead investing a modest sum to take a minority stake. Three of its investees are massive, well-established firms – two of which, in Thailand and the Philippines, are fintech services created by mobile phone networks.

Clik here to view.

A vendor in India takes payment via Paytm. A customer can scan the QR code from their phone to initiate the transaction. Photo credit: Paytm founder, Vijay Shekhar Sharma.

Only in India did Jack Ma’s crew entrust their largesse to a scrappy startup. Paytm, maker of an app not dissimilar to Ant’s Alipay, was the first overseas foray in early 2015, which it then doubled down on with further funding to truly cement the partnership. The Paytm bet has paid off, with the app growing to 150 million active users making an average of 7 million transactions per day.

Western Union arch-rival Moneygram, meanwhile, is an old hand, active in its present form since 1988, but with roots that go back to 1940.

4. Online shopping is just a small detail in the big picture. For now, anyway.

Given that Ant’s Alipay app is a spin-off from Alibaba’s marketplaces, you’d think the global expansion would be based on online shopping. But that’s not the case.

The focus is very much on web-based financial services – whether it’s extremely simple things like wiring money or topping up your phone credit, or more complex services such as loans or getting stores to accept Apple Pay-esque payments through phones.

Betting on fintech taking off before ecommerce.

Ant has plenty of experience in all those things from the China market, where Alipay has 450 million active users, making it the top mobile wallet app. It’s used for online and in-store payments, ordering takeaway, paying bills, transferring money, ride-hailing, loans, personal investment funds, insurance, lottery tickets, charitable donations, cinema tickets, book doctors’ appointments – and a ton more stuff.

For Ant’s expansion, online shopping is a mere sideshow. For now, at least.

That’s because its new customers are mostly in emerging markets, where ecommerce is still at an early stage. The company is betting on fintech taking off before ecommerce.

It’s plausible that, at some point in the near future, Ant’s payments and Alibaba’s tentative overseas ecommerce ventures will unite in some fashion in a bid to challenge Amazon.

5. Export all that fancy financial technology it’s honed over the years in China.

Although Ant isn’t seeking to build up a worldwide finance empire under the Alipay brand, the Chinese firm has tech and experience from its vast home market that it can export as it taps new countries.

In Korea, for example, Ant’s tech will manifest itself through its investee-partner, Kakao Pay, a soon-to-launch spin-off from the KakaoTalk messaging app. In India, Ant is turbocharging the engine behind Paytm, teaching the startup tricks about cashless payments that it has perfected over the years in China.

It’s a different form of global expansion than we see from Uber and Facebook. It’s less monolithic, more cautious.

The Chinese behemoth isn’t just exporting its financial services – it’s also spreading its “risk control, cloud computing” know-how, said Ant yesterday in its Korean announcement.

Ant’s own mission statement describes it thusly: “To collaborate with local partners through technology transfer, to make the financial services more accessible.”

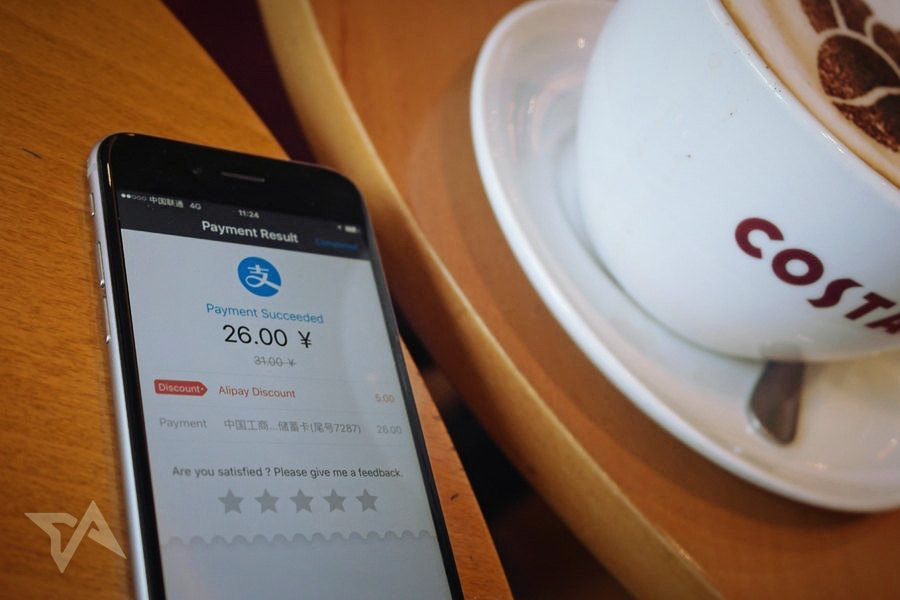

Clik here to view.

Alipay app shown after being used to pay for coffee in China.

Alibaba has a similar strategy as it slowly and quietly goes global. It acquired Lazada to tackle Southeast Asia, keeping the name of the only shopping site to have made a big impact across the fragmented region. In the US, Jack Ma’s company changed tack, opening its own store under a new name in 2014, but that was sold off after a year of seeing little traction.

6. Get more data. Big data. Bigly data. Lots of data.

With 1 billion transactions per day, Alipay has no shortage of data on its customers’ financial lives.

And as Ant expands and gathers more data, it gleans new information that helps it optimize its financial products.

Online loans give a clear example of this. In countries with no widespread credit scoring system, companies need to turn to unconventional data to weigh up an individual’s or small business’ riskiness – with social media activity, buying habits, and other online behavior often the preferred way to do that.

Ant might soon have the power to create its own credit scoring system for India and much of Southeast Asia.

Indeed, its Alipay app has already done so in China, with a credit scoring service that pulls in data from Ant Financial and Alibaba services, among other institutional sources. That score affects loan applications within the app.

However, some observers, including the ACLU, have sounded alarm bells over the free speech implications of tying important services to what you say online.

Funded AF

Jack Ma’s playbook will be seen in future investments and acquisitions by Ant. And there will be many – the company has vowed to reach two billion customers globally by 2025.

It’s already some way along that path, with a combined 600 million in China and India alone.

During expansion, the firm will remain flexible, picking services according to what each nation needs.

“We are leading first with payments and related services but we may very well offer other products and services market by market,” said Ant’s senior vice president Douglas Feagin late last year after branching into Thailand.

Ant raised US$4.5 billion in April last year to fund Chinese as well as global expansion.

This post Inside Jack Ma’s playbook for Ant Financial’s global expansion appeared first on Tech in Asia.