Islamia College in Peshawar. Photo credit: sakhaphotos / 123RF.

The city of Peshawar, located in Pakistan’s northwestern region, tends to make headlines for the wrong reasons. It’s just a two-hour drive from the capital, Islamabad, but also the last major urban centre before one enters the loosely governed tribal areas bordering Afghanistan.

In recent years, the city has borne the brunt of the state’s fight against religious extremism and terrorism, with reprisal attacks against government and security installations.

Things have calmed down since last year, but this troubled narrative belies the rich cultural history of Peshawar. Its origins date as far back as 539 BC, making it one of the oldest surviving cities in Asia. It was once the capital of the Gandhara civilization and still houses many ancient Buddhist monuments and relics. Conquerors like Alexander the Great have trekked across this land.

The city has traditionally relied on an endless stream of migrating merchants, large bazaars, and a smattering of industry as the primary drivers of its economy. But the internet has well and truly permeated public life in Peshawar as well as the larger province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP).

During my visit to the city last month, I saw evidence of how the web is changing lives: small businesses use it to sell products across the country. Ordinary citizens glean vital information from Facebook. WhatsApp video calls are an important way for overseas workers to stay in touch with family members back home.

The internet’s economic potential is real and not going unnoticed.

That’s important because the province is in desperate need of jobs. Estimates suggest Pakistan has lost US$118 billion due to fewer investments, lower exports and taxes, and non-existent tourism as a result of the ongoing war on terror. Even local institutional investors are reluctant to invest in Peshawar in the fear that their business interests might be harmed.

Shahbaz Khan, Head of the KPITB. Photo credit: KPITB.

Man on a mission

Leading the charge to digitize the province of KP, impart digital literacy, and encourage entrepreneurship and freelancing is Shahbaz Khan. He holds a doctorate in computer systems engineering from the UK and has almost a decade of experience working in academia and industry-funded research.

Shahbaz’s passion lies in wireless devices and multispectral imagery, but that’s taken a backseat for now as he aims to galvanize the public sector, work with universities, and build co-working spaces. He’s been trying to do that since June, following his appointment as the head of the KP IT Board (KPITB).

The province needs a systemic shift in the way it approaches its digital future.

I meet Shahbaz in his squeaky-clean but modest office located in the heart of Peshawar. Unlike other bureaucrats in the province, Shahbaz doesn’t have any airs or pretensions. He’s friendly, warm, and willing to learn from others. The door to his office remains ajar and one doesn’t need to schedule a meeting in advance.

Most people in his position would have refused to occupy the same workspace as he does – government jobs in Pakistan come with demands for luxurious offices, personal secretaries, and imported SUVs. Shahbaz wants none of that.

He’s also accommodating. People scurry around him constantly – someone needs a signature on a large cluster of files, another requires feedback on an upcoming project. Shahbaz says he is careful not to come across as rude or abrupt lest his staff feel as if they’re working in another typical government department.

“It’s necessary to have a team you can absolutely trust,” says Shahbaz as he furiously chain-smokes Dunhills. “When I came in, the entire department was riddled with inefficiencies – in fact it’s hard to say we had a team at all. I had to make a lot of changes.”

His view of the tech landscape in KP is straightforward. The province needs a systemic change in the way it approaches its digital future – the quality of university graduates needs to be improved, investors have to be given incentives to set up manufacturing and outsourcing hubs, and the government must do more to forge partnerships via co-working spaces and digital literacy programs.

Shahbaz Khan meeting with the World Bank team. Photo credit: KPITB.

Part of the technical assistance behind this project of digital inclusion is provided by the World Bank’s social development department. They’ve been working closely with Shahbaz and his team to make sure all stakeholders come together and there’s minimal bureaucratic hurdles.

The focal points of the project are creation of jobs and opportunities to capitalize on youth expectations, but there’s also a concerted effort to improve access to public services, healthcare, banking, and education.

“There’s a lot of expectations from us,” admits Shahbaz. “We’re trying our best to succeed.”

Upskilling

One of the first areas of focus for Shahbaz has been to help the large population of freelancers in Peshawar and adjoining cities. He refers to them as “low-hanging fruit,” and a way to create the maximum short-term impact.

It’s a pertinent move – Pakistan has, by some estimates, the third-largest population of freelancers in the world, doing things like website design and app development, closely tailing the United States and India. Examples exist of some earning as much as US$20,000 per month and Shahbaz insists he knows others with a monthly income of as high as US$65,000.

“It’s important to groom these people further, teach them skills that will be relevant in the coming years, and assist others who want to follow similar paths,” he affirms.

Shahbaz knows what he’s talking about – he’s dabbled in freelancing even after completing his PhD – and understands that it’s a powerful tool to open up jobs where they’re desperately needed.

The goal is to build a mini-Shenzhen in Pakistan.

To assist with this, the KPITB has built four co-working spaces which they call “Durshal,” or ‘gateway’ in the local language. These spaces aren’t just fancy offices – Shahbaz calls them “community innovation labs,” – where there’s ongoing training and workshops on topics ranging from communication skills to app development. The eventual goal is to have Durshals in far-flung areas of the province as well. Recent graduates can apply to attend, completely free of charge.

“Previous administrations built a lot of universities but there wasn’t enough emphasis on relevant digital skills and training. We have to overcome this challenge,” he insists.

Durshal Peshawar also houses the Civic Innovation Fellowship – a six-month program where techies work with government departments to improve citizen engagement and solve issues in areas like disaster management, transportation, crime, traffic, and healthcare.

An inside view of Durshal. Photo credit: KPITB.

Latching on to Chinese presence

Shahbaz’s long-term strategy is to build a mini-Shenzhen in Pakistan. And he’s dead serious about achieving that goal.

The premise behind this project is the China Pakistan Economic Corridor – a US$57 billion commitment by the Chinese government to build roads, power stations, railway networks, and special economic zones across the entirety of Pakistan. It’s part of the global One Belt, One Road initiative. Work is moving ahead at full steam.

It’ll result in thousands of new jobs.

“It’s in our hands to make sure this is more than just a transportation corridor,” Shahbaz tells me. “We need to work with the Chinese, and encourage their companies to set up manufacturing plants here, otherwise we run the risk of falling behind.”

To achieve this, Shahbaz says he’s employing a multi-pronged approach. He’s hired a full-time employee in Beijing simply to ramp up negotiations and explore potential areas of collaboration with large Chinese conglomerates. There’s serious interest from their end, he claims.

Brands like Oppo, Huawei, and Lenovo are already household names in Pakistan. Xiaomi launched in February. The country has approximately 40 million 3G/4G subscribers, with over a million new connections added every month. IDC estimates that over 6 million smartphones were shipped in Pakistan in 2016, with the number expected to rise sharply in the coming years.

There’s surging demand for consumer tech but no local manufacturing to speak of. Almost all the smartphones, tablets, and PCs available in the country are imported. Shahbaz points to this dynamic and says there’s innumerable potential just to cater to local needs – it’ll result in greater hardware expertise, lower prices due to reduced taxation, and the creation of a support ecosystem.

Crucially, it’ll result in thousands of new jobs.

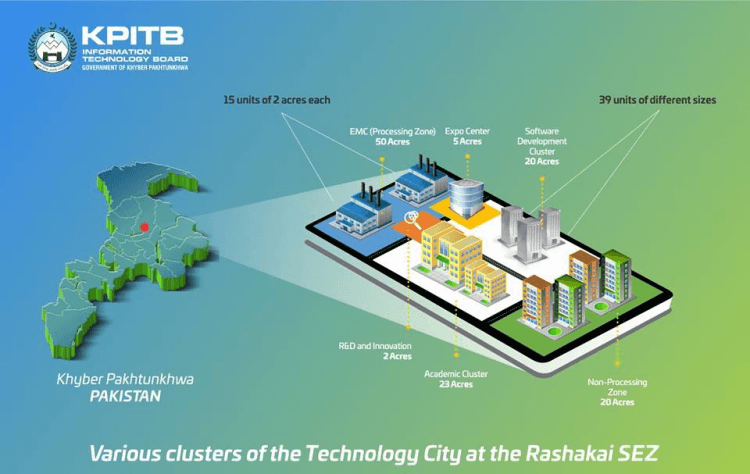

And these aren’t just pipe dreams. The KP government has already acquired and allocated 100 acres of prime industrial land to support the creation of a ‘Technology City.’ Negotiations are underway with Foxconn, Xiaomi, Huawei, and Oppo to move some of their manufacturing to this economic zone. It’s too early to say whether it’ll happen for sure, but Shahbaz remains confident.

He tells me he’s already started putting the necessary support systems in place to make sure his vision of a manufacturing hub comes to fruition.

“Look at Shenzhen – one of the reasons it’s been able to succeed and grow is because of investment in universities, research, and cutting-edge tech. We need to do the same,” he explains.

“We’ve started talking with Tsinghua University and Peking University to establish a joint venture on ground here. Ideally, we want them to partner with a local university and have a dual-degree program. We can scale this model after understanding best practices and learnings.”

Map of the proposed ‘Technology City.’ Photo credit: KPITB.

Startups matter too

Talk about entrepreneurship and building products is important, admits Shahbaz, but he believes that the entire ecosystem needs to come together before they can be truly successful.

He points back to freelancers – many of those are building apps and websites for Western clients and feel the model can easily be replicated in Pakistan. What’s holding them back is that they don’t have supporting networks in place in case they fail. Many of these ambitious graduates come from desperately poor families and need a steady, stable source of income.

Entrepreneurship appeals to them, but they have to eat too. That’s why the government needs to do its bit to change attitudes.

The startup movement in KP is not stagnant, however. There’s Peshawar 2.0 which aims to channel local creativity and talent towards relevant ideas. Its first cohort of companies graduated recently.

Another social enterprise incubator is Tech Valley Abbottabad which recently organized a tourism conference and announced it would be focusing on travel tech for the short-term.

Both incubators want to encourage founders to set up camp in KP, attract investors, and push for a focus on digital businesses.

“The major problem some of these startups will face is access to capital because of the prevailing disconnect,” says Shahbaz. “We’ve started work on a platform that’ll connect wealthy members of Pakistan’s diaspora to commercially viable ideas – like a matchmaking facility. Once it’s implemented, we expect the number of startups to grow manifold.”

This post After the war on terror: an ancient Pakistani city looks to tech for its revival appeared first on Tech in Asia.