Lines at ATMs are common in India after PM Modi’s announcement. Depleted ATMs are often marked by signs saying “No Cash.” Photo credit: Monito.

On November 8, I was walking back from grocery shopping in the near-dark when I noticed something weird – people were queued up at every single ATM I passed. My spidey senses alerted – I had just used nearly the last of my cash – I checked my phone. I had three messages from different people warning me that come midnight, all INR 500 (US$8) and INR 1,000 (US$15) bills were going to be rendered useless. ATMs, which tended to spit out money in 500s and 1000s, weren’t going to work for the next 48 hours.

India’s cash-first economy had opened the door for corruption and black money – illegally obtained, untraceable, and therefore untaxable cash – said the country’s prime minister Narendra Modi. Taking this step would propel India forward into a digital economy and surprise those hoarding illegal bills. People had gotten, at most, four hours’ notice. I got two.

See: Why India’s demonetization is the biggest disruption for electronic payments in 2016

My friends assured me I should do nothing. Everything would be fine.

The next day, around noon, I tried and failed to pay my part of a group lunch bill (international cards were not accepted, I was to find out, at the majority of local shops and startups where I normally took my business – we’ll come back to this later). I realized things weren’t going to be fine. Over the next month, living in Bangalore took on an existential quality – endless lines at the ATMs and old notes being turned into paper sculptures, with no quick end in sight.

See: Why India took such a drastic step to go cashless

Beyond tech startups

Photo credit: Michael Coghlan.

I don’t think people outside India fully understand the extent to which demonetization had on daily life in India, if at all. So the country got some new money – so what?

Tech in Asia’s first look, of course, was at Indian tech startups, which were thrilled. Fintech startups like Paytm all but danced on rooftops with the promise of new business. Even startups that relied on older methods of exchange like bartering saw a boost. But that’s only a small part of the picture.

‘Why don’t you just Paytm your maid?’ ‘My maid doesn’t have a smartphone.’

As the weeks went on, it became clear things weren’t going exactly as planned. The endless lines at the ATM didn’t dry up. A student, not able to withdraw cash payment for his exams, committed suicide. One friend lamented that he had to leave work early to stand in line at the ATM because he had to pay his maid.

“Why don’t you just Paytm your maid?” the person next to him asked.

“My maid doesn’t have a smartphone,” he answered. That’s not unusual. Neither does 83 percent of India.

This is anecdotal evidence, of course, but is also an indication that the full consequences of such a quick switch weren’t thought through.

See: Paytm is laughing all the way to the bank

What it was like

To put things into perspective, what does demonetization look like? Imagine that, overnight, the two highest bills available in your country were rendered void. In the US, the two highest bills in circulation are the US$100 and US$50 bills, but ATMs usually dispense money in increments of US$20. So pretend that all three of those are banned.

Knowing the majority of people in the country aren’t rolling around in illegal money, banks give you around two months to return the invalid money you have. That’s a pain in the ass. Because now you and everyone on your block is in line at the bank, trying to exchange that money. This sucks, but things even out, and you eventually get used to using your card for everything. (A new INR 500 bill [US$8] and an INR 2,000 [US$30] bill have since been produced, but that took a couple months – and good luck getting anyone to give you change.)

For reference: India has the largest unbanked population in the world.

That’s lucky for you. Because 47 percent of people in your country don’t have bank accounts. For reference: that’s the largest unbanked population in the world. So 95 percent of business is conducted in cash, and 90 percent of vendors are unequipped to process any other method of payment. Cash is the sole method of payment for 85 percent of your country’s workers.

This can include, but is not limited to, your landlord, your maid, and your drinking water delivery boy. These people don’t necessarily speak your language or the local language, and if you don’t pay them, they can’t pay for themselves. So you stand in line at the ATM. You have a withdrawal maximum of US$30 to US$40 per day. The ATM maybe stocks at 8am and is out of cash by 10am (or, if you’re lucky, you hire a startup employee to stand in line for you).

If you happen to be overseas at the time, your bank imposes nearly the same daily cash withdrawal limit on you that it does on everyone back home. If you happen to be a tourist in India – tourism accounted for US$136.3 billion of India’s GDP in 2015 – you suddenly can’t get any money out of the ATMs. Rickshaws only take cash. Ola doesn’t take international cards. Uber works, but that’s an American service, not an Indian one. The street food stall doesn’t accept international cards, but Starbucks does.

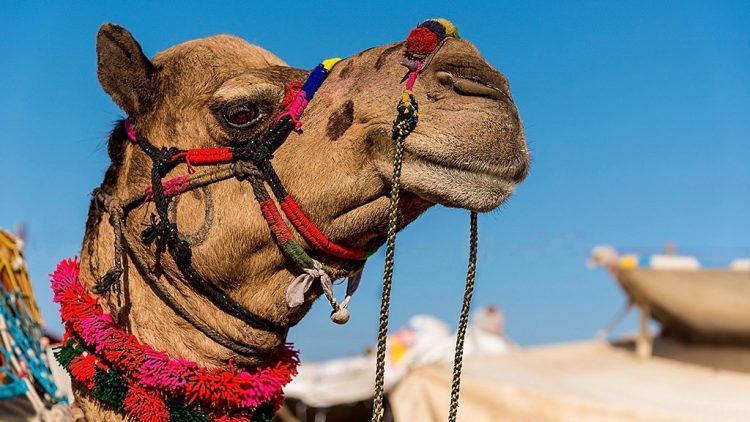

Tourism was up at November’s Pushkar Camel Fair in Rajasthan, but sales were hard to make, as camel owners looking to sell only took cash. Photo credit: Koshy Koshy.

Demonetization was as much a surprise for banks worldwide as it was for everyone else. They stopped dealing in Indian cash immediately, meaning one of the few options open to tourists – and me – was bringing foreign currency into the country and exchanging them for the new bills. That works fine for me because I have that option. Those people getting paid only in cash? Not so much.

Transitions take time. Remember when you couldn’t look at international news without hearing about the transition the US went through when it signed a new healthcare bill (Obamacare) into law? India has roughly four times the amount of people, and while not everyone in the US had to sign up for the healthcare marketplace, which was directed toward the lower income bracket, everyone in India was affected by demonetization.

And what’s more? We’re not even sure if it worked.

The cash crunch breakdown

According to BloombergQuint, 86 percent of India’s circulated currency was invalid as of four days before the demonetization announcement. 59 percent of this invalid currency was returned, with no permanent way of determining how much of this was illegal to begin with. There is no secure figure yet on how much black money was curbed by the cash crunch.

What’s more, “black money” doesn’t always mean “cash.” Nearly US$14.9 million exchanged hands in real estate less than a week after demonetization took effect. Just because money is on the books doesn’t mean those books are accurate. Additionally, demonetization also doesn’t touch the money hidden in offshore accounts.

Demonetization fucks over the working class.

So maybe demonetization puts a dent of mysterious size in upper-class black money movers. It’s an inconvenience to the middle class. But it fucks over the working class – the rickshaw drivers, the guy who brings you water, and the lady who owns your trusty but tiny corner store. I got a taste of this because I, like half of India, don’t have an Indian bank account. Foreign friends of mine who tried to get one when demonetization hit were still waiting on paperwork to come back six weeks later.

Say that unbanked half of the country manages to get bank accounts – or get bank accounts with their mobile numbers. That’s still roughly half a billion unbanked people. Small businesses would have to upgrade to take cards – which may or may not involve having additional transaction fees. That takes time and money away from a lot of these people who can’t afford to lose either.

Much of India – including startups – operates off cheap labor. Photo credit: Jeff Peterson.

In the meantime, a foreigner like me further fucks over the working class. Right now, if the local business doesn’t accept my international Visa or MasterCard, I straight up can’t pay – I have to take my money to bigger businesses that’ll process my payments.

See: Why tech fixes are not the answer to India’s developing world problems

Open to attack

Finally, more money flitting around digitally means a greater risk for cybersecurity breaches. Arguably, this risk comes with the reward of a cashless society, but it’s not a fight easily won. The US$81 million Bangladesh Bank heist in February last year is not the last time digital money – and a lot of it – is going to be compromised. (And let’s not forget that last year a single power outage grounded a Fortune 500 airline.) Demonetization – crowds of people opening bank accounts, exchanging cash, and signing onto fintech services – is a hacker’s paradise.

“We invest millions of dollars a year in data security – it’s one of the big risks of digitalization,” cross-border payments startup Payoneer CEO Scott Galit tells Tech in Asia. If there’s opportunity, hackers will come – ready or not.

If there’s opportunity, hackers will come – ready or not.

(None of these problems are new, by the way – Sweden is having the same ones, and the country of around 9.5 million people – 0.8 percent of India’s population – has been transitioning slowly toward going cashless for years.)

To avoid being the Bangladesh Bank, financial institutions around the world are upping their defenses, so how secure are fintech startups? On December 16 – a little more than a month after demonetization took place – Paytm filed a complaint concerning 48 users abusing its return and refund policies. If India truly wants a cashless society, it’s going to need to up its cybersecurity defenses quickly.

India’s IT minister has ordered strengthened measures in the wake of online security breaches by Legion, an Anonymous-like group in December. The whole world is fighting a digital battle.

Overall, demonetization, ironically, isn’t as much of a money issue as it’s an issue of time. Particularly in a population of 1.2 billion, a decision so monumental has to take all parties into account, and this one clearly didn’t. So while tech startups are enjoying some of the perks of a digitalized economy, it’s a good idea to remember that tech doesn’t always extend to the working class.

Meanwhile, the clock is ticking, and things still aren’t fine.

See: App-less in Bangalore: how I went grocery shopping as the city simmered

This is an opinion piece.

Converted from Indian rupees. US$1 = INR 67.14

This post I was caught in the middle of India’s demonetization move. Here’s what I learned appeared first on Tech in Asia.